Your Basket

Oops! Your basket is empty

At Huel, we want to change the way people think about food, and our company’s mission is to make “nutritionally complete, convenient, affordable food, with minimal impact on animals and the environment”.

Many of our meals come in the form of powders which you turn into shakes at home (as well as snacks, drinks, nutritional top-offs, and hot meals). Eating this way might look pretty different from what you’re used to. So is Huel healthy?

To find out, we conducted a rigorous scientific study. The central question for the research was, essentially, ‘is Huel good for you?’ In 2022, the results of our study were published in the peer-reviewed journal Frontiers in Nutrition.

Related: The health benefits of Huel

Huel is nutritionally complete food. This means that every Huel meal contains a perfectly balanced mix of protein, essential fats, carbs, fibr, and all 26 essential vitamins and minerals. But while that all sounds great on paper, what does it actually mean for your body? Is Huel actually good for you? Are there any side effects of Huel? And is Huel’s promise – healthy food that’s affordable, convenient, and delicious – too good to be true?

In collaboration with our independent researchers at Aelius Biotech, experts in conducting human research trials, we put Huel to the test in a scientific trial.

We know, based on thousands of other studies and government guidance, that the nutrients Huel contains should lead to improved health outcomes. But we wanted to discover specifically how eating Huel affected the body. So we asked 20 participants to eat only Huel for four weeks while we monitored their levels of specific markers of health – chemicals in our body that offer a reliable barometer of things like metabolic health – as well as vitamin and mineral status.

(In normal life, Huel is made for your most inconvenient meals, not every single meal. But, since this was a scientific study we wanted to control as many variables as possible to ensure the results were reliable.)

The findings were so impressive that they were accepted for publication in the widely-trusted Frontiers in Nutrition journal. You can read the full article here, but below you’ll find a slightly more digestible (sorry) explainer.

This trial was an extension of exploratory in-house research — ’Project-100’ —which detailed the effects of consuming Huel as the sole source of nutrition for five weeks.

Thirty generally healthy adults were enrolled in the trial, 20 of whom (11 females, 9 males, a median age of 31 years) completed the study, with 19 sets of blood samples collected. (It’s typical for a trial such as this — which requires people to be extremely disciplined with what they eat — to expect a dropout rate of a third. It’s not easy to consume just Huel and water for four weeks, which is why we recommend choosing it for your most inconvenient meals, not every meal).

Participants were asked to complete a food diary before they started the intervention stage of the trial (that is, the lead-in week) to see how they usually ate. This showed researchers things like their average daily calorie intake. The research team also used this to calculate the amount of Huel each participant should be consuming per day to maintain their weight during the trial.

Each participant was then tested, twice: once before the trial started (week zero) and then again after the lead-in week (week one). The tests included blood sampling, body mass index (BMI), visceral adipose tissue (VAT, the fat that lines internal organs), and body composition testing (measuring things like the amount of muscle, fat mass, and water someone consists of). This gave researchers their baseline health metrics so that they could see each person’s health markers changed during the 100%-Huel diet. Essentially, each participant was acting as their control.

All participants were then asked to consume only Huel Powder v3.0 for four weeks, with only water, black coffee, and non-citrus teas being the exceptions. Participants were also asked to fill in a food diary to capture how much Huel they were ingesting throughout the trial. Blood sampling, BMI, VAT, and body composition were tested again after four weeks (that is, in week 5 of the trial).

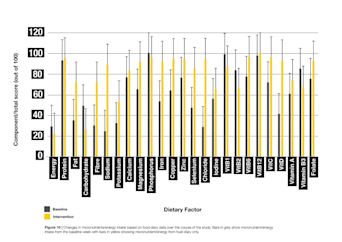

Below are the 22 markers that were tested from the blood samples:

Haemoglobin

Sodium

Calcium

HbA1c (an indicator of average blood sugar level)

Total cholesterol

HDL (High-density lipoprotein or “good” cholesterol)

Non-HDL cholesterol (all the “bad” types of cholesterol)

Iron

Vitamin A

Vitamin D

Vitamin E

Vitamin C

Vitamin B12

Choline

Magnesium

Potassium

Zinc

Copper

Manganese

Selenium

Thyroid-stimulating hormone

Learn more: What are the health benefits of all these nutrients?

So, what were the effects of a Huel-only diet? Throughout the study, 14 of the measurements significantly changed.

Lower energy intake with Huel: During the four-week Huel-only diet, none of the participants met their recommended energy intake. There are a few reasons why this might have been, not least the fact that Huel contains lots of protein and fibre, which have been shown to keep people feeling fuller for longer (and thus decreasing appetite). But despite lower than advised energy intake, most of the nutrients still improved during the intervention in comparison to baseline.

Iron increase: Haemoglobin and iron were both statistically higher after the four-week Huel diet.

Lower cholesterol: Total cholesterol and non-HDL cholesterol were significantly lower post-intervention at both week 0 and week 1.

Blood glucose changes: HbA1c, used to assess blood glucose levels over a sustained period, significantly reduced post-intervention at both week 0 and week 1.

Blood vitamin changes: There were significant reductions in blood vitamins A and E, as well as potassium, throughout the trial, but measurements for these nutrients still remained within the normal, recommended range.

Vitamin increases: Levels of vitamins B12, vitamin D, and selenium significantly increased from the two baseline measurements to the final measurement at week 5.

Weight changes: Overall, BMI, VAT, and waist circumference all significantly decreased after the four-week Huel-only diet.

VAT changes: Three of the 20 participants showed an increase in visceral adipose tissue (VAT) after four weeks on Huel, whereas 13 participants showed a decrease in VAT, and four showed no change.

Waist circumference changes: Throughout the trial, two of the twenty participants showed an increase in waist circumference, whereas 16 showed a decrease. Two participants showed no change.

Is Huel good as a meal replacement? Our study answers that question with a resounding ‘yes’.

On most measures, the data gives a fairly conclusive answer to anyone wondering whether Huel is healthy.

But as with any peer-reviewed scientific study, some interesting and slightly unexpected results are worth looking at closely.

Energy intake

Even though the participants were advised to eat enough Huel to maintain their body weight, calculated from their baseline week energy intake, the data suggests that their actual calorie intake during the four weeks was consistently below the recommended amount. This energy restriction may have resulted in an improvement in some parameters of health (especially body weight and cardiometabolic parameters such as blood glucose, and cholesterol). However, what is also interesting is that despite people consuming fewer calories — and therefore less Huel — than was recommended, the intake of most nutrients still improved.

Total and non-HDL cholesterol

These metrics are known risk markers for coronary heart disease and diabetes — the lower these numbers, the lower the risk of developing these conditions. Baseline values showed that seven out of the 19 participants started the trial with high total cholesterol. The decrease in total and non-HDL cholesterol following the four-week Huel trial is encouraging, however, the reason for this could be due to both the nutritional profile of Huel and the weight loss that was observed. Huel is plant-based and therefore contains a relatively low amount of saturated fat. It also contains phytosterols from flaxseeds, which other research has suggested may reduce low-density lipoprotein (LDL – ‘bad’ cholesterol)[2-3].

HbA1C

Otherwise known as glycated hemoglobin, HbA1C is a form of hemoglobin that is linked to a sugar molecule. Haemoglobin is a protein in your red blood cells that carries oxygen around the body. HbA1c is a good marker to indicate the average blood sugar levels. If HbA1c levels are too high then the risk of developing type 2 diabetes increases. There were significant improvements in blood glucose markers following four weeks on Huel. That suggests an enhanced glycaemic control, which is linked to the reduced risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

The authors also reported that the inclusion of acerola cherry powder in Huel v3.0 powder may also have antihyperglycemic effects, meaning that it limits the uptake of glucose from carbohydrate digestion and thereby dampens increases in blood sugar[4].

Vitamin B12

Levels of vitamin B12 significantly increased after four weeks of eating Huel. One participant presented as deficient in B12 at baseline but was within the minimum recommended levels at week five. This is especially good news for vegans, as vitamin B12 – which is important for metabolism and brain function – often comes from animal-based sources, so a vegan diet can be deficient. Even though Huel powder is plant-based, B12 is added in the micronutrient blend in the form of cyanocobalamin. One 100g serving of Huel powder provides 32% of the recommended daily intake.

Vitamin D

Before the four weeks of an all-Huel diet commenced, 58% (11/19) of the participants had suboptimal vitamin D status, which significantly increased to within the recommended range by the end of the trial. Huel v3.0 powder contains 80% of the minimum recommended daily intake of vitamin D in each 100g serving. Vitamin D is important for the immune system and for the health of bones, teeth, and muscle function[5].

Selenium

Overall selenium increased following the trial, with one participant starting below the recommended level. Their levels increased to within the optimum range by week 5. Huel v3.0 powder contains 36% of the recommended daily intake per 100g serving and is important for things like healthy hair and nails.

Iron and haemoglobin

Iron is an essential ingredient in hemoglobin (around 70% of the iron in our body is found in our blood) which is why healthy levels are important for things including cognitive function, oxygen transportation, and reducing tiredness and fatigue. After four weeks of consuming Huel, levels of both iron and haemoglobin had improved significantly, which on the one hand isn’t surprising – oats, peas, and brown rice protein provide 57% of the minimum recommended daily intake in every 100g serving.

On the other hand, it is surprising that these numbers improved so much considering that plant-based – or non-haem iron – isn’t absorbed as well as iron from animal sources (6-8), especially considering that oats contain an ‘anti-nutrient’ called phytic acid, which can slow the rate of absorption even further [9]. Likely, the high levels of vitamin C in Huel (75% of the daily recommended value per 100g) helped here, as studies have shown that it can improve iron absorption significantly [10-11].

Vitamins A and E, and potassium

Measures of these vitamins and potassium decreased over the course of the four-week Huel diet. So is Huel bad for you if it leads to a decrease in certain vitamins? Not necessarily.

This result is less concerning than it initially sounds. Some participants started the trial with both vitamins above the recommended daily intake – by the end, all participants were within the optimal range of vitamins A, E, and potassium.

Huel v3.0 powder contains 23, 2.5, and 35% of the daily recommended intake respectively for vitamins A, E, and potassium per 100g serving. Vitamin A is good for healthy skin and vision and vitamin E helps to protect the body from oxidative stress. Potassium can help with muscle function, blood pressure, and a healthy nervous system.

Body Mass Index (BMI)

Even though BMI data isn’t the most reliable way to estimate body fat (because it’s based on height and weight, and muscle is more dense than fat, so elite athletes can end up in the ‘obese’ category) it can be a helpful indicator for ordinary people. BMI measurements work by taking a person's weight in kilograms and dividing that by the square of their height in metres. The score is then categorised as either ‘underweight’, ‘healthy weight range’, ‘overweight’, or ‘obese’, which shifts slightly based on their age.

Baseline values suggest that 63% (12/19) of participants had excess body weight by BMI. However, following four weeks of Huel, BMI had significantly decreased - suggesting it can help with weight loss.

Waist Circumference

Generally speaking, waist circumference can correlate with obesity, as well as someone’s amount of VAT and their risk of developing cardiovascular diseases. It is also an indirect marker of insulin resistance [12-15]. Waist circumference significantly decreased following four weeks of consuming Huel [16].

Visceral Adipose Tissue (VAT)

VAT is the amount of fat surrounding the body’s organs. Too much VAT is generally bad news – it’s an independent risk factor in cardiometabolic diseases such as coronary heart disease, stroke, and hypertension [16]. Overall, after four weeks of Huel, VAT decreased compared to baseline.

We’re pleased with these results. They show, pretty conclusively, that Huel is healthy on a wide range of measures.

But as ever with scientific research, all the things we discovered have only suggested yet more avenues to explore. Firstly, there’s the question of energy intake. Even though participants were advised to eat a specific amount of Huel to maintain body weight during the trial, the data suggest that their total intake decreased over the four weeks. This self-elected energy restriction resulted in a reduction in body weight in some of the participants.

Ensuring participants ate enough calories for weight maintenance is important, as it means that we could more accurately understand which health outcomes were purely related to Huel, and which were because of energy restriction.

We also don’t intend Huel to be eaten as a sole source of food. That means that there is scope to explore the impact of eating different amounts of Huel. For example, is Huel healthy when eaten, say, twice a day, or twice a week, alongside a standard diet? This would give us more insight into the real-world benefits of Huel within wider dietary habits.

Another interesting avenue for further research would be about Huel’s effects on gut health and the microbiome. As we conduct more studies into the ways Huel is good for you, we’ll keep publishing the results, so you can make the most informed decisions for yourself.

Wilcox MD CP, Stanforth KJ, Williams R, Brownlee IA and Pearson JP , . A Pilot Pre and Post 4 Week Intervention Evaluating the Effect of a Proprietary, Powdered, Plant Based Food on Micronutrient Status, Dietary Intake, and Markers of Health in a Healthy Adult Population. frontiers. 2022.

Baumgartner S, et al. Effects of a Plant Sterol or Stanol Enriched Mixed Meal on Postprandial Lipid Metabolism in Healthy Subjects. PloS one. 2016; 11:e0160396.

Bierenbaum ML, et al. Reducing atherogenic risk in hyperlipemic humans with flax seed supplementation: a preliminary report. J Am Coll Nutr. 1993; 12(5):501-4.

Hanamura T, et al. Antihyperglycemic effect of polyphenols from Acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC.) fruit. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2006; 70(8):1813-20.

Aranow C. Vitamin D and the immune system. Journal of investigative medicine. 2011; 59(6):881-6.

Gregory J. Anderson GDM. Iron Physiology and Pathophysiology in Humans. Humana Totowa, NJ: Springer; 2012.

Beck E. Essentials in Human Nutrition. edition t, (eds). 2012.

Hallberg L. Iron requirements and bioavailability of dietary iron. Experientia Suppl. 1983; 44:223-44.

Minihane AM RG. Iron absorption and the iron-binding and anti-oxidant properties of phytic acid. International Journal of Food Science & Technology. 2002; 37:741-8.

Lane DJ, et al. The active role of vitamin C in mammalian iron metabolism: much more than just enhanced iron absorption! Free Radic Biol Med. 2014; 75:69-83.

Teucher B, et al. Enhancers of iron absorption: ascorbic acid and other organic acids. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2004; 74(6):403-19.

Park J, et al. Waist Circumference as a Marker of Obesity Is More Predictive of Coronary Artery Calcification than Body Mass Index in Apparently Healthy Korean Adults: The Kangbuk Samsung Health Study. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2016; 31(4):559-66.

Borruel S, et al. Surrogate markers of visceral adiposity in young adults: waist circumference and body mass index are more accurate than waist hip ratio, model of adipose distribution and visceral adiposity index. PLoS One. 2014; 9(12):e114112.

Alberti KG, et al. The metabolic syndrome--a new worldwide definition. Lancet. 2005; 366(9491):1059-62.

Reeder BA, et al. The association of cardiovascular disease risk factors with abdominal obesity in Canada. Canadian Heart Health Surveys Research Group. Cmaj. 1997; 157 Suppl 1:S39-45.

Ruiz-Castell M, et al. Estimated visceral adiposity is associated with risk of cardiometabolic conditions in a population-based study. Scientific Reports. 2021; 11(1):9121.

Get the scoop on exclusive offers and product launches.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply. You can unsubscribe at any time. Huel Privacy Policy.